For the first part of this series click here

For the second part of this series click here

For the third part of this series click here

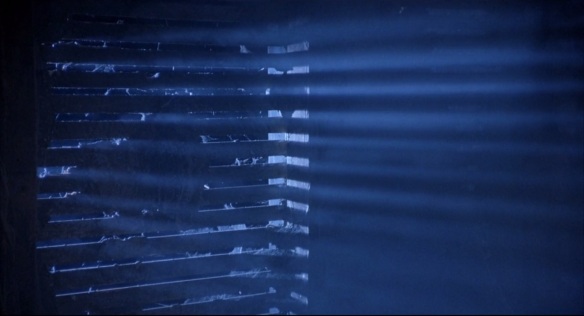

Repulsion (1965) Roman Polanski

It was in 1968 that Roman Polanski really took hold of popular cinema, with the resources of Hollywood helping him to craft a horror film shot in broad daylight, intertwining the supernatural with mundane domesticity. That film was Rosemary’s Baby and although it was an introduction for many to Polanski’s work, it was not his first polished piece. Indeed that film formed the middle section of the so called ‘Apartment Trilogy’, each focusing on dreadful elements bubbling below the surface of the domestic. The first film in that series was Repulsion, made in the UK, which provided Polanski his first foray into English language cinema.

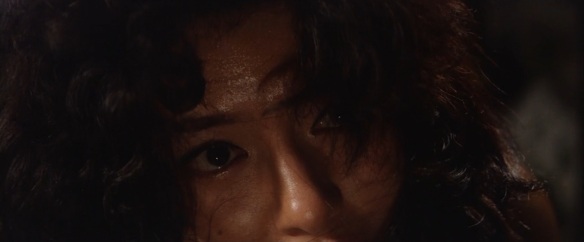

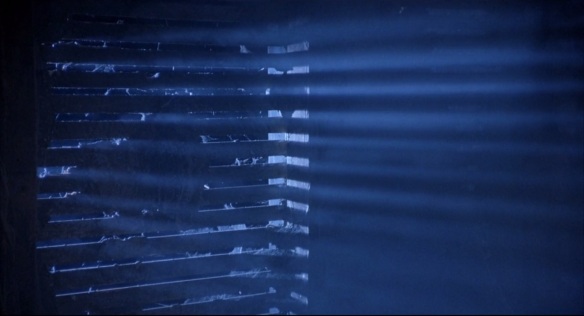

Providing the focal point for the film we have Carole (Catherine Deneuve), a young French girl currently living in London with her sister. She’s pretty but delicate, almost a wisp blown through the streets of the city. She works in a beauty salon and, despite her shy nature, all seems well. To a certain degree it’s difficult to provide a full account of the storyline beyond that. The details are apparent but the specific causality is far more difficult to grasp. Seemingly because of her sister’s lover, a married man, spending an increasing amount of time at the apartment, and perhaps also fuelled by another man’s attempts to court her, Carole begins to slowly lose grip of her sanity as deep-rooted sexual dread begins to surface. When her sister and lover vacation in Italy for a week they leave Carole to mind the apartment, and it grants her sanity just the seclusion it needs to crumble away entirely.

What marks Repulsion out as a truly superior psychological thriller is the refinement of Polanski’s direction. Not a shot or sequence seems out of place and the film maintains a steady, measured pace as we follow Carole’s nightmare- taking its time to grant us our bearings so that their loss will resound all the more. Behind the camera was Gilbert Taylor, a man who has worked with everyone from Alfred Hitchcock to Stanley Kubrick to George Lucas, and no other film better represents his mastery of black-and-white photography (no, not even Dr. Strangelove). His work lends a tactile dimension to the images that enhances both their inherently mundane quality and also the inexplicable air of threat they present to Carole. Minimal levels of special effects are used and, where they are employed, they are kept simple, usurping this sense of surface. The smooth walls turn to malleable clay in one scene, the walls crack violently, and a simple cutthroat razor never seemed more loaded with dreadful potential.

The violence here is perfectly measured, made potent by the investment we have in the characters. Coupled with the often explosive percussion score, mundane sound effects, such as a ticking clock, form the aural backdrop. Nothing here seems outlandish. It is Carole’s own dysfunction that colours the apartment with so much venom until we reach that closing shot; a textbook example of the cinema’s unique potential. It reminds me of the economy and power of the final shot of Mizoguchi’s Ugetsu– a world of suggestion and potential in a single move of the camera. Where so many psychological thrillers offer glib explanations for their antics, deflating the intensity of what preceded, Polanski opens the question to the audience. Should they dare, they may explore at their leisure.

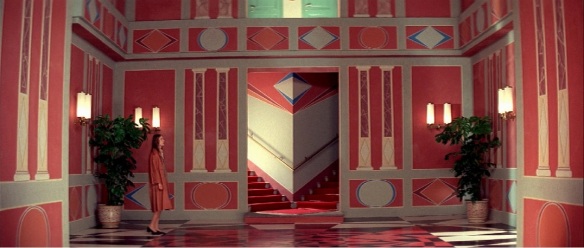

The Night of the Hunted (1980) Jean Rollin

Do you enjoy episodes of The Twilight Zone but find yourself wishing there were more nude French women? Yes? Really? Well then I may have a movie recommendation for you. For those unfamiliar, Jean Rollin was a French director who made his name with surreal, erotic vampire films that were generally bereft of both funding and coherence. Still, he was a unique force, crafting films that, whether you enjoy them or not, you must concede could only be his. Although he seldom shifted away from vampires – albeit, like Jess Franco and other euro-trash stalwarts, he also dabbled in hardcore pornography to pay the bills – when he did it often resulted in his best work. The late-70s and early-80s stand out as a Belle Époque for Rollin and, coincidentally or not, overlaps with his casting of Brigitte Lahaie, one of the breakout stars in a freshly legalised French pornography industry.

The Night of the Hunted hosts a threadbare narrative but gives full voice to the Rollin’s romantic inclinations. Indeed, this is an unapologetically romantic film, with a man seeking to reconnect with a young woman held captive in a specialised facility. She is held here with others, all of whom deteriorate from the same, unnamed affliction. With an urban setting, a narrative hinging on degenerating humans, and a carnal undercurrent that occasionally bubbles to the surface, a surprising analog emerges in David Cronenberg’s formative cinema, primarily Shivers and Rabid. These works share a strong affiliation in both theme and atmosphere. It seems evident that Rollin took cues from the young Canadian. Another curious overlap is that Rabid also featured an actress who made her name in pornography, the late Marilyn Chambers (horror fans might also note that Chambers can be glimpsed in The Exorcist, on a box of Ivory Snow laundry detergent). Lahaie is undoubtedly the more charismatic performer and although the film opens with an extended sex-scene, her central role builds into a fully realised performance.

And they lived happily ever after?

What’s so unusual here is the melancholy Rollin finds within what might otherwise seem the typical horror milieu. As minds deteriorate, reducing human function to the bare necessities, Rollin finds his core romantic thesis, a kinship that pushes through the conscious and outlasts it. He offsets this against the doctors of the film, trying to cure this horrible malady, which intones that most terrifying of afflictions, Alzheimer’s, who, due to their inability to legitimately help, find themselves rationalising ever more heavy-handed intervention, up to and including euthanasia. It’s revealed that their motives stem from more than just medicine but from politics and subterfuge too. The world is all too brutal but Rollin, without a vampire in sight, still finds beauty to fill the film’s final moments.

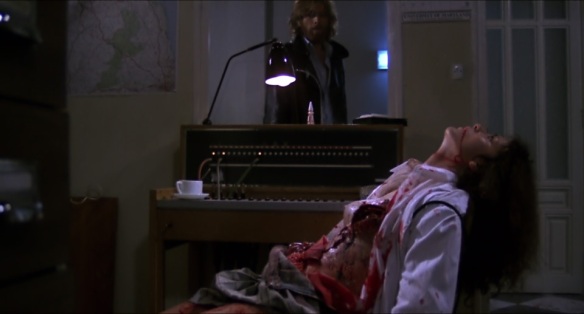

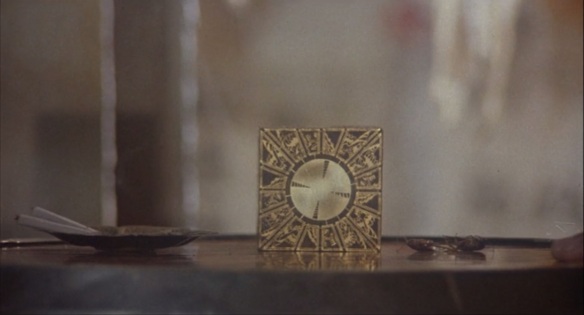

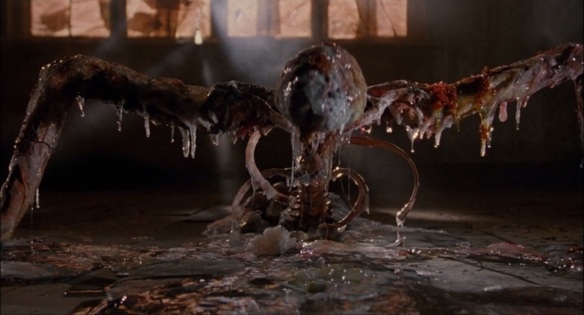

Hellraiser (1987) Clive Barker

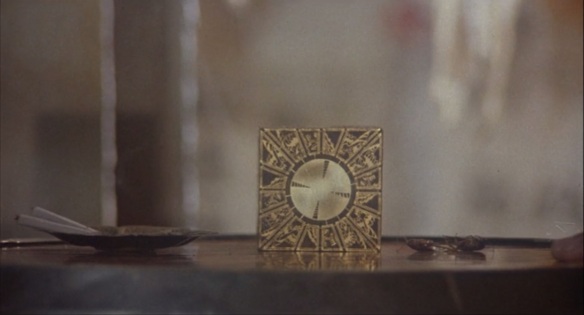

So I’ll admit Hellraiser might seem a bit obvious for a list like this. It’s haunted plenty of people in my age demographic since before we even saw it, on those days when you’d head to the videostore with your parents and inevitably wander over to the horror section to soak up the lurid VHS cover-art. You’d always find Doug Bradley’s Pinhead staring back at you, his bald head sectioned off with countless nails driven through: the perfect fuel to set alight young nightmares. You hardly even had to watch the film but I, of course, eventually did. I’ve always liked it but it’s only been in recent years that I have come to herald it as one of the finest of all horror films, a claim I don’t exactly make lightly. I guess that over the years it has bled under my skin and sunk its steel hooks into my brain.

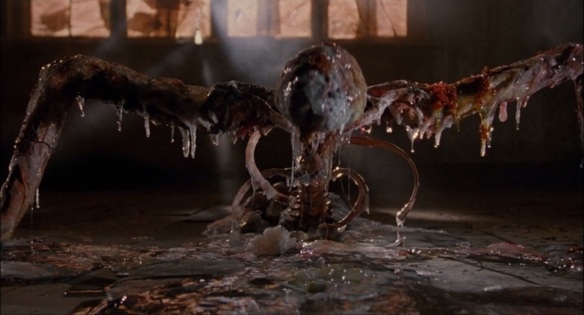

This is not to say that Barker’s film is not without its flaws, it certainly has a few and some of them are significant. Exhibit one is the daughter, Kirsty Cotton (played by Ashley Laurence), who Barker uses as a stand-in for the audience, a vessel through which to give us viewers a peek inside an intensely private affair. It’s an understandable move, but misjudged, and it distracts in the later passages, where Kirsty’s actions become narrative fulcrums when we’d all rather wish she’d just not be there instead. It’s a problem specifically because Hellraiser is a tale of interiors, not least because almost its entire narrative is pinned not simply to a single house in bustling London, but to a single room within that house. There resides the final traces of a man whose deadly impulses destroyed him and, through an omission by forces he can scarcely understand, he sees the possibility to regenerate and rejoin the truly alive. For that he needs living flesh to consume, and to get that, he needs the help of his former lover, now married to his brother. Luckily for him, old passions die hard, and she reciprocates, driven by her own unfulfilled passion. But of course, it was the tenacity of passion that led him to his downfall to begin with, and so the cycle now begins anew, with unwary new players taking to the field.

Why are you in this damn movie?

It is the intensity of the core love-story, a tale of truest l’amour fou, which drives the film. Although surface details now look undesirably dated with the heady mistakes of 80s fashion excess, in a sense these are almost a boon, preserving the film in time as the period details of Poe serve to preserve his. When so steadfastly trapped in time, the stories assume a timelessness. It’s just that since many of us remember the 1980s and not the 1880s, the details may distract. Digging beneath, the intensity of the performances, the slow, levelled delivery of lines and the deadly deliberation of the central players all speak to a grand, fatalist romance- something entirely in line with the aforementioned Poe and classic tales of human folly. The Cenobites, of which Pinhead is merely the most outspoken, but certainly not the leader, remain a most brilliant visual invocation of carnal human desires- the titillating lust for experience and to sate deep-rooted desires. They are not villains, but contractual actors, opening the door for what humans already accommodate. Their suffering, in S&M-infused horror, is that their brief dalliances with some sweetly sexual agony have become their eternities. They now serve to wreak that hell on others, though only if they’re asked…an offer laced with irresistible potential that some will always indulge.

Barker’s original is a tragic tale of sullied romance first and a gory shock-fest second. It is a superb rendering of the dark linings of human sexuality, packaged as monster movie. It isn’t Barker’s fault that his schema was so alluring that it produced, indeed demanded, sequels. Making a sequel to Hellraiser is as absurd as penning a follow-up to The Raven (Hellraiser 2? Nevermore!) but of course it had to be done. The franchise is mostly daft, trying to fill in backstory and follow narrative inquiries that were of no relevance to begin with. While a few sequels managed, almost accidentally, to find small plateaus of success, the vast majority sink under the heavy stone of redundancy. I guess their failure only mirrors the deadly mechanics of the Puzzle Box that links our world with that of the Cenobites. A delicately constructed Trojan Horse, it’s alluring enough that you just have to keep going, even though your mind screams that you’re only going to make it worse.

And if you’d like to indulge in a Hellraiser sequel then I’ll still help you out.

The Wicker Man (1973) Robin Hardy

Another obvious choice, I suppose, for those to whom such a film is already a favourite. I have found though, since moving to the United States, that this film’s cult there is greatly reduced, and that for many casual film fans, even those with a penchant for horror cinema, the risible Neil LaBute remake is often what springs to mind. We’ll speak no more of that remake, other than to remark that it is entertaining, though not quite on purpose, and is otherwise so directionless that it hardly overlaps with the original’s immense shadow. The original remains one of the oddest, most effective, and impressive horror films of British cinema.

We open with a mystery: a policeman (Edward Woodward) arrives at a small, privately-owned island off the coast of Scotland. He is responding to an anonymous tip that a young girl has gone missing. The tightly-knit populace of the island offers him little assistance. At first they don’t recognise the girl in the photo and later they say she died a few months back. No one seems to remember just how she died. As the policeman continues his inquiries, growing increasingly frustrated with what appears to be an indifference to his case laced with conspiracy, he also becomes aware that this picturesque isle harbours some unusual traditions which chafe his staunch Christian faith. A meeting with the owner of the island, Lord Summerisle (Christopher Lee) confirms that the agrarian community is founded on the tenets of ‘The Old Gods’ and maintain a pagan way of life.

Shot mostly in daylight, and entirely devoid of spooky goings-on or shock cuts, The Wicker Man seems a world apart from what most of horror cinema claims as its own. Indeed, the film could almost claim status as a musical, stringing together a series of beautiful, bawdy folk tunes as the villagers enmesh the policeman in their rituals. This soundtrack, with the songs all embedded in the film’s events, not simply overlaid a-top the images, is not simply a pleasant adornment to the film but rather a central pillar of the whole project. With their heavily sexualized lyrics they recall age-old concerns of courting, procreation, and just plain fun, that served humankind as an early compass through life. It was only with later incarnations, Christianity and so forth, that sex became a matter of some impropriety, begrudgingly acknowledged but best not spoken of. This unease between Christian and pagan mores, writ larger as a showdown between the civilized and otherwise, sets the tone for the whole film and no matter how pretty the little town may be, as an outsider it is quickly veiled in uncertainty and threat.

The Wicker Man cleverly condenses various antagonisms of western history into a strange tale of a missing girl. It trades not on shocks or on violence but on the slow realisation of being truly at odds with your environment you bereft of control. Woven between are threads of music and humour which reward repeat visitors. There really is nothing else quite like it and the later American remake somehow managed to even more boldly highlight the original’s iconic status.

Death by Hanging (1968) Nagisa Oshima

Yes, Oshima actually has made a ghost story, the eerie Empire of Passion from 1978, but in a brilliant career, this is probably his scariest and indeed his most brilliant film. Granted, it’s not ghosts or ghouls or monsters or unsuccessfully aborted conjoined twins hell-bent on revenge. No, it’s much worse than that. It’s politics.

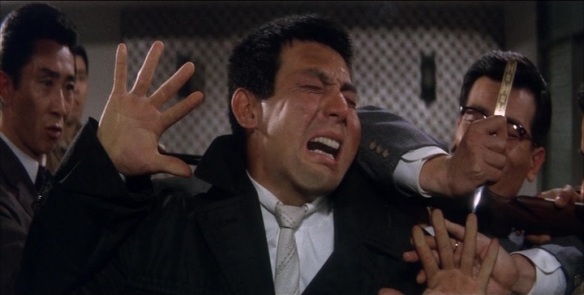

A showcase of Brechtian technique, Oshima’s film is highly experimental in tone and slips free of any constraints one might normally expect of narrative cinema. A man, a Korean, has been sentenced to death by hanging for the crime of murder. He is hanged but, somehow, he does not die. Instead he loses all memory of himself and his crimes. The presiding officials from the Japanese prison and government are left in a precarious position. They could try and hang him again but questions are raised about the ethics of hanging a man with no recollection of his crimes, and thus no guilt. Of course within this framework Oshima has his eyes on grander questions: the legitimacy of state violence; the nature of crime and guilt, both personally and nationally; and quite specifically, as was a long-time concern of his, the perceived mistreatment of Korea by Japan.

With the criminal unable to recall his crimes, the next step is to recreate them, with the various officials crudely acting out his crimes in front of him, so that he might rekindle at least enough memory that they could execute him. It’s absurd and deeply uncomfortable stuff, humour dyed in the deepest vein of black. As the law-abiding officials re-enact the prisoner’s crimes, emphasizing repeatedly his status as a Korean living in Japan, their own violent histories, again both personal and historical, bubble through to the surface.

Oshima’s film is a searing political document and a loaded gun that begs answers from anyone interested in political institutions and their mechanics. Although immersed in a very specific national identity, that of Japan, the questions of crime, guilt, punishment, and state action invariably concern us all. That I include it on a list of horror films is simply because the stakes could never be higher than here and Oshima’s film, with its overtures to Kafka (this would make an ideal double-bill with Orson Welles’ superb incarnation of The Trial) paints a troubling portrait of institutionalised violence and society’s very real tendency to ignore deep-rooted problems to instead focus on superficial punitive measures.

The Last House on the Left (1972) Wes Craven

There are a lot of revenge movies in the world. Thousands. Tens of thousands, even. I’ve seen my fair share. Some are good. Some are bad. Some are really bad. Most are slack-jawed entertainment, doused in authoritarian mores. Some are smart and look inward. Some are allegorical tales of inter-generational conflict and national identity. Okay, maybe that’s just Ermek Shinarbaev’s remarkable, Revenge. Anyway, out of all those films, only one is The Last House on the Left. And if you’re wondering if that film is good or bad, the truth is, it’s more complicated than that.

Introducing the world to writer/director Wes Craven, The Last House on the Left is a low-budget, grim re-envisioning of no less lofty a source material than Ingmar Bergman’s The Virgin Spring. Now sure, I like A Nightmare on Elm Street as much as the next man, but what business has Craven got tackling Bergman? Actually, he has quite a bit of business, making a film that is, if not an unreserved triumph like Bergman’s, nonetheless a troubling little beast of the burgeoning American grindhouse movement. In the early-70s, independent American cinema was still struggling to define its boundaries, answering to market forces by pushing violence and sex freely in the wake of the recent dismissal of the censorious Hays Production Code. American filmmakers were free to go places they previously couldn’t and plenty of the films of that time feel quite a bit more unrestrained than contemporary cinema’s slicker, more market-oriented product. Above all of those, stands Craven’s film, with levels of transgression that feel dangerous even today.

The story is unremarkable, a young woman and her friend are heading to ‘the city’ for a concert when they are confronted by a trio of escaped convicts. The girls are kidnapped, sexually humiliated, raped, and ultimately murdered. The criminals move on only to later cross paths with the parents of one of the girls. Vengeance is meted out and all seems normal per the genre’s understood code. What is unusual is the severity of Craven’s representation of events and the film’s own uneven tone. These factors highlight difficult concerns in exploitation and violent cinema generally, leaving the audience with a whole heaping of discomfort and difficult questions. It’s neither here nor there that Craven probably didn’t intend it that way.

The final, horrific moments of the two girls are paraded in front of the audience with no distinction drawn between the base titillation of naked flesh and the supposed scenario which is unfolding; that of rape and butchery. There is nothing subversive at work here. The murderers’ wishes to sexually humiliate the girls are passed straight on to the audience. It’s a near unthinkable reality but it’s pretty riveting up there on the silver screen and Craven’s camera peers steadfastly onward as the horror slowly unfolds. What’s really odd is that Craven then intercuts those scenes of sexual sadism with slapstick details of bumbling cops and a genteel folk soundtrack. It’s likely these elements were designed to inject some levity into proceedings, with Craven conscious that the MPAA were going to bitch-slap this film for its gruesome content (and also for it not being a major studio production- a sin the MPAA never forgive, while cruelly dangling a rating in front of industry outsiders) but the balance is decidedly wrong.

Relentlessly vicious cinema can be taken simply as a bitter pill but Craven’s attempts to defuse the nastiness actually make the film harder to process. I seriously doubt that was his aim but it certainly makes his film stand out. And so this film seems genuinely dangerous. As if Craven knew he shouldn’t but couldn’t help himself. As if the camera in his hand made him do it. So all that is wrong is what is so right here. The breezy soundtrack, the idiot cops, the absurdity of its “justice”, and the genuine exploitation at the core of it all. I can’t say I like The Last House on the Left but it remains emblazoned in my memory when so many similar projects from the time have faded.