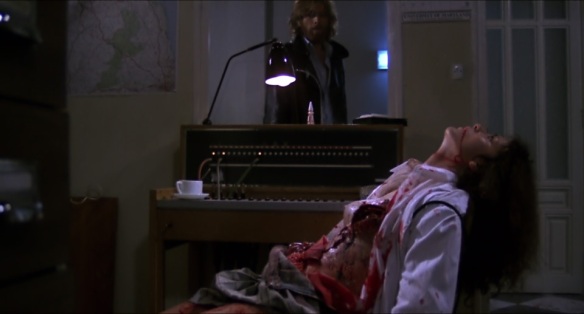

The Church (1989) Michele Soavi

The Italian horror circuit through the 70s and 80s was a pretty small troupe, but who could complain with such talent? The movement was on the decline through the 80s but it’s fair to say that Michele Soavi had been picked out as the front-runner to cut the path into the 90s. Alas, that never really came to pass, for reasons I’m unsure of. Soavi still works to this day but he’s not made a horror film in two decades now. Perhaps the industry’s downturn quashed too many avenues, perhaps he just grew disinterested in it, I don’t know. What I do know is that Soavi’s early career as a horror director is marked by a couple of fabulously entertaining features.

He started as an assistant to Dario Argento, sometimes even appearing in front of the camera too. You can find him in Bava’s A Blade in the Dark, for example. Eventually he graduated to helming feature films of his own and opened with the hyper-stylized StageFright. Despite a close overlap with a Hitchcock title, StageFright vs. Stage Fright, rest assured it would be impossible to mistake the two, what with the synth-pop soundtrack and an axe/drill-wielding killer who wears a giant owl-head for the whole thing. Yeah, it’s pretty great. Still, it’s Soavi’s second film that I’ve chosen, because it’s arguably his best.

Considering the people he trained with, the slow-burn aesthetic of The Church might feel surprising. In fact it was originally intended as a second sequel in the growing Demons franchise until Soavi wisely nixed the idea. He wanted to break free and craft something more reserved and atmospheric. The Demons films, the first two at least, are massively entertaining but they are not what we might call subtle. Indeed, if they were faced with subtlety, they would smash its head to a bloody mush against a wall while bopping along to a blaring heavy metal soundtrack.

The Church follows more in the footsteps of Argento’s free-form supernatural thriller, Inferno, although it does so with a much quieter, haunting aesthetic. And where Argento unhinges from narrative, assaulting viewers with a sensory barrage, Soavi remains engrossed in story, slowly ratcheting up the tension. The spectacle, ancient demons made manifest, is impressive and employed sparingly, heightening their effect. Meanwhile the soundtrack, a Keith Emerson score dotted with Goblin and Philip Glass compositions feels perfectly appropriate. Soavi’s sensibilities are, in many respects, more careful and mature than we could have any right to expect, and expand on the work of his formative influences, staking out his own place in the pantheon of Italian horror.

The Living Dead at Manchester Morgue

Everyone seems to love zombie movies. They’re everywhere and everyone is touting their fandom. Discussions on the internet revolve around people imagining how they might survive a zombie outbreak and how excited they are that The Walking Dead is coming back on the air. While I’ve nothing against zombie movies, indeed I could count myself as a fan too, it always surprises me that, amidst this popular love of the genre, so few people seem to have seen anything outside of Romero’s original trilogy, a couple of other modern knock-offs, and the aforementioned The Walking Dead– each episode of which, based on my own cursory viewing, seems to be a 50/50 split between boring shots of people shooting zombies and those zombies then falling over, and irritating, whiny morons whining moronically about their irritations.

Without a shadow of a doubt, Romero looms large over the genre and his original trilogy of films, Night of the Living Dead, Dawn of the Dead, and Day of the Dead are the definitive texts of the modern genre, but his work also gave rise to a number of talented impersonators. The European zombie movement took off with a vengeance, in part fueled by Romero’s close work with Dario Argento. The Italian horror/exploitation scene was running wild in the 70s too, producing so many films it’s difficult to keep count. A few stand taller than the rest though, with Lucio Fulci’s Zombie Flesh Eaters aka. Zombie aka. Zombi 2 (in Italy a ‘2’ was appended and it was marketed as an unofficial sequel to Dawn of the Dead) commanding a pretty good audiences. Less well known is an Italian/Spanish co-production, shot in the UK, that boasts so many varying titles I believe it actually may have set a record. We’ll call it The Living Dead at Manchester Morgue as that’s the one I’m most familiar with, although you may also find it listed as: The Living Dead; Let Sleeping Corpses Lie; Don’t Open the Window; Do Not Speak Ill of the Dead; and various variations on all of those.

Without a shadow of a doubt, Romero looms large over the genre and his original trilogy of films, Night of the Living Dead, Dawn of the Dead, and Day of the Dead are the definitive texts of the modern genre, but his work also gave rise to a number of talented impersonators. The European zombie movement took off with a vengeance, in part fueled by Romero’s close work with Dario Argento. The Italian horror/exploitation scene was running wild in the 70s too, producing so many films it’s difficult to keep count. A few stand taller than the rest though, with Lucio Fulci’s Zombie Flesh Eaters aka. Zombie aka. Zombi 2 (in Italy a ‘2’ was appended and it was marketed as an unofficial sequel to Dawn of the Dead) commanding a pretty good audiences. Less well known is an Italian/Spanish co-production, shot in the UK, that boasts so many varying titles I believe it actually may have set a record. We’ll call it The Living Dead at Manchester Morgue as that’s the one I’m most familiar with, although you may also find it listed as: The Living Dead; Let Sleeping Corpses Lie; Don’t Open the Window; Do Not Speak Ill of the Dead; and various variations on all of those.

There’s nothing particularly glaring about the film’s production to make it stand out amongst the throngs of other cheap, quickly produced movies of the era but, take my word for it, The Living Dead at Manchester Morgue is easily one of the finest zombie movies ever made. It’s a fairly traditional affair, relying on the excitement of escaping from the zombies more than on dubious allegory to fluff up its ingredients. It finds our heroes desperately trying to stay alive as the living dead come to haunt rural England. What distinguishes the film is the quality of its set-pieces, which combine satisfying levels of gore with a strong sense of narrative tension and excitement. Unlike countless other zombies, there’s a real feeling of urgency to this one, coupled with strong design.

Also, it features the line, “You’re all the same the lot of you, with your long hair and faggot clothes,” which maybe my favourite line in all of movie-dom (you have to hear it in context). Doom Metal group Electric Wizard also liked it, sampling the line to open their song, Wizard In Black. Granted, this nugget of information will almost certainly never help anyone ever. But just in case, I thought I’d better include it anyway.

Bay of Blood (1971) Mario Bava

In the last article I did in this series I talked about the grand shadow cast by Mario Bava. He was a giant in Italian cinema and one of the most influential genre filmmakers around. First establishing himself as a cinematographer, he later became a director in his own right, presiding over a series of popular Gothic horror films including the brilliant Black Sunday (aka. Mask of Satan). As his career progressed, he helped to shape the tenets of what would be known as giallo, a sub-genre of films, distinctly Italian, that gelled mystery with gory, highly stylized murders- invariably involving blades and scantily-clad women. Growing weary of these films, and using his own money, Bava decided in the early 70s to try something a little new. So one day he kinda invented slasher films, as you do.

Although it’s exact origins are tricky to pin down exactly, since bloody death had been a mainstay of cinema for a while already, there’s little doubt that without Bava, what would become known in the US as ‘slasher films’ simply would not exist. To that end, Bay of Blood was a formative start to the movement, defined by narrative so pared down that it frankly bordered on the abstract. Although the template is well set now, there was a time when a group of people showing up in an isolated place and all being summarily slaughtered in various different ways wasn’t justification enough for a film to unfold. Weird, right? It was Bava’s tale of a contentious inheritance in a small lakeside community that cheekily demonstrated that sometimes, killing’s all you need (The Beatles claimed it was ‘love’ but they hardly seem trustworthy).

Given its extreme violence and rudimentary narrative Bay of Blood was a shock to the system at the time, prompting many horror fans to discard it as a completely inane gore-fest. Sure, that’s what 99% of slashers are, but Bava’s film, brimming with paranoia, does build a legitimately interesting result, suggesting a pernicious fate which, in the film’s conclusion, transcends familial and generational lines. The slasher film as a kind of filmic ‘standard’ would be cemented in due course, but Bay of Blood is perhaps the earliest clear adherent to the format, supplanting narrative justification (a mainstay of giallo) with ever more brute force. The result remains one of the finest slasher films ever made. Indeed, maybe even the very best of them all. And in the US it got the rather fabulous title of Twitch of the Death Nerve.

Vampyr – Der Traum des Allan Grey (1932) Carl Theodor Dreyer

Dreyer is generally regarded as one of the finest directors in the history of cinema. That’s fairly understandable since that’s exactly what he is. However while much attention is lavished on the likes of The Passion of Joan of Arc (which is, to be fair, an easy contender for the title of greatest film ever) and Ordet, his bizarre 1932 horror film Vampyr is often forgotten. I say it’s a horror film but it’s altogether stranger than that: a kind of lucid dreamscape involving a man possibly encountering a vampire, being ensnared by it, or simply passing on to the other side himself. Pick your interpretation, the film remains intensely watchable regardless.

Although time is often unkind to films beyond a certain age, Vampyr’s washed-out look is partly by design. Discovering a light-leak in the lens early into the production, Dreyer asked the cameraman not to fix it because he liked the diffuse, hazy look it gave the film. Elsewhere he shot through gauze to texture the image, all of which only heightens the oneiric bent of the exercise. Disinterested in narrative logic, the film assembles a fabulous array of odd and intriguing visuals, conjuring up spectres of death in the oddest of places. As mentioned above, the film can be interpreted allegorically or can be followed in more literal, and decidedly supernatural, terms.

Thought-provoking and atmospheric, there really aren’t many equivalents to Dreyer’s film, which remains a crystallised dream from so many years ago. In many respects, the film is timeless, harnessing the eccentricities of the production, some intended, some not so much, to create a project that stands apart from both Dreyer’s other work and cinema in general. Its influence can be traced through to David Lynch and others but it remains a singularly important work all of its own and a necessary trip for all of cinema’s dreamers.

The Pendulum, The Pit, and Hope (1983) Jan Švankmajer

If you’re stuck for time but would like a quick shot in the arm, then this one’s for you. Created by Jan Švankmajer, one of the world’s finest animators, here he adapts Poe’s The Pit and the Pendulum, conjuring up an abstract, nightmare vignette set in labyrinthine tunnels with a deadly, bizarre apparatus threatening the unnamed protagonist. Using primarily live action, the film blends in his trademark stop-motion techniques to filter the otherworldly into the frame.

Staying close to the original text’s style, Švankmajer seeks to heighten the experiential by presenting the entire film in a first-person perspective, the lens of the camera literally the eye of the tortured protagonist. This blends with the claustrophobic set design and the details of hideous minutiae to create a particularly jarring and atmospheric rendition of the tale, perhaps the best ever filmed.

The Face of Another (1966) Hiroshi Teshigahara

The sixties was a great decade in general for paranoid identity studies. Though spoiled for choice, it would be easy to nominate Japan’s Hiroshi Teshigahara as their king. The Woman in the Dunes is probably his best known film though my preferences tend more towards his later film, The Face of Another. Alongside Pitfall, they form a loose thematic trilogy on the subject of fractured minds, societies, and identities.

The story concerns an engineer whose face is badly disfigured in an industrial accident. He becomes reclusive and angry, unable to deal with this injury. Things look up when a doctor offers him an experimental treatment, essentially a lifelike mask that can replace his entire face. The only issue is, since his face is destroyed, it will have to be another man’s that forms the model. This doctor’s office is a completely abstract space, free-floating and amorphous, and the discussions there wax more philosophical than medical. Concerns are raised that, with a new face may come new behaviours and indeed, perhaps an entirely new identity. These concerns are well met as our protagonist, recognizing the potential to start entirely anew rather than rekindle his old life, begins to adopt increasingly aberrant behaviours.

Teshigahara’s film is visually gorgeous, appropriately utilising black-and-white despite it being somewhat out of vogue by the mid-sixties. His father being a master of Ikebana, the traditional art of floral arrangement that branched, often literally, into huge and remarkable organic sculpture, Hiroshi was entirely at home in the avant-garde and unusual. To that end he surrounded himself with a bevy of experimental artists, adapting novels from the acclaimed Kōbō Abe, with cinematography by Hiroshi Segawa, set and prop designs by noted architects and sculptors, and a musical score by Toru Takemitsu. It is a formally bold film, with its intellectual concerns writ neatly into its every nook and fold and stands as one of the high-points of 60s cinema, in Japan and elsewhere.

For the first part in this series click here