For the first part of this series click here

For the second part of this series click here

For the third part of this series click here

For the fourth part in this series click here

Maniac Cop 2 (1990) William Lustig

For those looking for a little action grit with their horror thrills, then there’s always the Maniac Cop franchise. I default to the part 2 because, well, it’s the best, but the original film is certainly no slouch and is also well worth a look. It’s not required viewing to enjoy the sequel though, which conveniently re-caps the first film’s finale by replaying it in its entirety. With William Lustig directing a script from Larry Cohen, this is entertainment first, with any high-falutin’ ideals about changing the world or challenging the status quo buried deep enough that no one need accidentally trip, although with its recurring theme of institutional corruption, you could get digging if you felt the urge.

Picking up right on the heels of the first film, the resurrected and thoroughly pissed off Maniac Cop (Robert Z’Dar) has been buried in the docks of New York (in one of the best stunts in American 80s cinema) and the police are left with a lot of questions to answer. They’ll be picked up by a hand-nosed detective (Robert Davi) and a cynical police psychiatrist (Claudia Christian) who unwittingly inherit the case when police officers start dying again. It’ll take more than the pollution in New York Harbour to kill this guy.

There are a few specific factors to recommend Maniac Cop 2, most notably its continuation of the superb stuntwork that distinguished the first film. Lustig credits himself with discovering Spiro Razatos and giving him free reign with the stuntwork and second unit direction and while Razatos had a number of credits to his name prior to this, this certainly was the ideal vehicle to showcase his talents. It’s immediately evident that Lustig and Razatos were watching a lot of Hong Kong action cinema of the time because they shoot for a similar low-fi, high impact aesthetic, with the stuntwork placing human bodies centrally in action sequences. This serves as a welcome alternative to the more usual, and more boring, Hollywood tactic of strategically dotting stuntmen around massive explosions that serve instead as the central spectacle. Everything that made Maniac Cop so impressive from an action standpoint is back in part 2 and inched up an extra notch, marking the film out as one of the best American action films during a time when Hollywood still actually made notable action films.

Elsewhere the film offers everything the viewer might expect with a steady pacing that never allows the meagre narrative to sag. As artfully composed as the action sequences are, Lustig injects intelligent ornamentation throughout, most notably the searching camera movement around a stripper’s apartment that wordlessly imparts all the details we need to recognise how far her reality strayed from her dreams. Sure, it’s not quite the revelation a similar shot was in Bob Rafelson’s Five Easy Pieces, but it’s a thoughtful touch and distinguishes this film from so much mass-produced junk that litters the low to mid-budget film circuit. Our Maniac Cop even makes a friend, a frothing, puritanical pervert (Leo Rossi) whose warped vision of the world makes him a fitting sidekick to a man so heavily fuelled by vengeance that he refuses to shuffle off his mortal coil.

There’s nothing genuinely new here, and no one could reasonably expect there to be, but Lustig and Cohen repackage the standard with plenty of individual touches, offering a quality product that can satisfy even hardened genre movie fans. Although the custom-written Maniac Cop rap song that closes out the film might be a bit of an overstep.

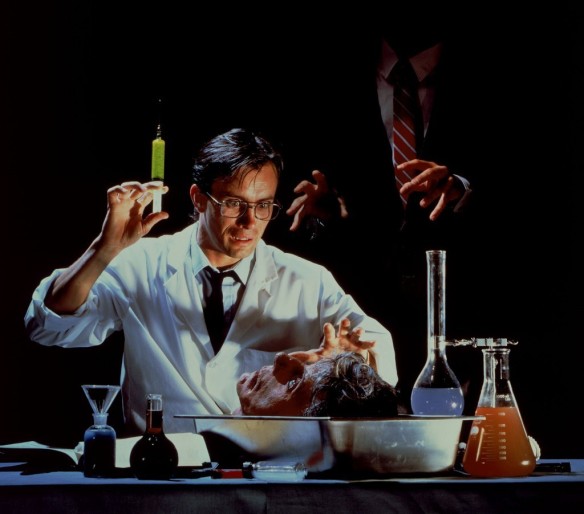

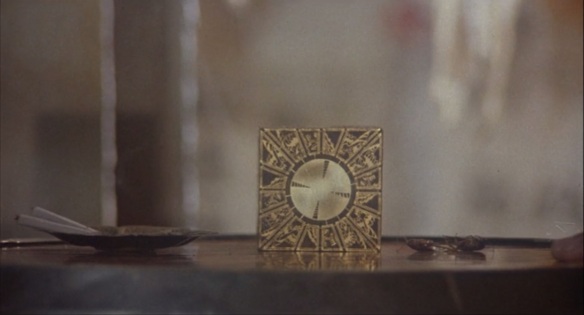

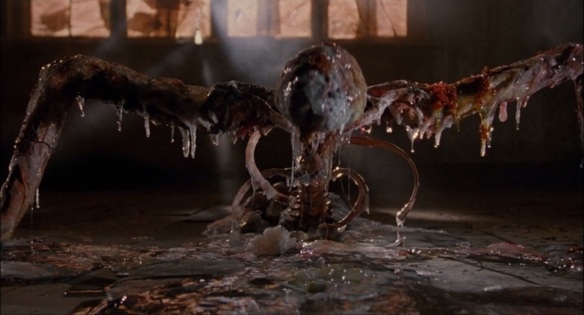

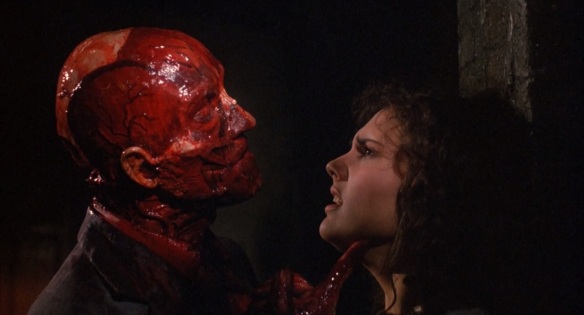

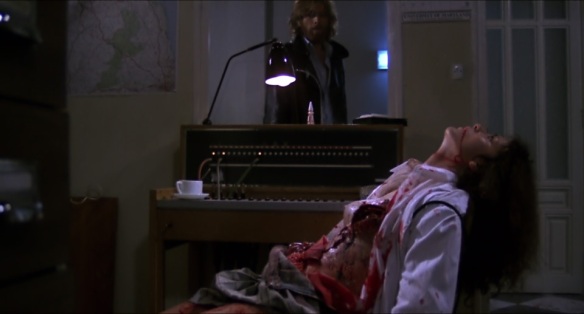

Re-Animator (1985) Stuart Gordon

As adaptations of H.P. Lovecraft go, we’d have to admit that Stuart Gordon’s 1985 film isn’t exactly the most faithful adaptation. That’s okay though, because the spirit is there and the final product remains one of the most grotesque and oddly humorous horror films around. Gordon’s done plenty of good work elsewhere and I admit, given Re-Animator’s fairly popular stature, I was tempted to talk up his excellent re-telling of Poe’s The Black Cat for cable horror series, Masters of Horror, or another of his Lovecraft adaptations, the underseen, and surprisingly effective Dagon. But there’s no denying that Re-Animator stands alone, his greatest work in a career that certainly hit plenty of bumps but has stayed an interesting course.

Much of the film’s success rests with Jeffrey Combs and his portrayal of the slightly mad student doctor, Herbert West, whose medical studies have pushed into areas the Hippocratic Oath could scarcely accommodate. West has developed a serum that can re-enervate dead tissue, effectively bringing the dead back to life. The only problem being that he can’t quite figure out the perfect dosage to restore not simply basic motor functions, but also higher intellectual functions. Pinning down this little detail requires a lot of experimentation and what West lacks in patience, he more than makes up for with access to a fully-stocked morgue. Cue the shambling dead.

Gordon’s film is high energy and fast-paced, pushing through its exposition and faux-science to ensure that some kind of bizarre spectacle is never too far from sight and all the right pieces are comfortably in place for the final meltdown. Despite this snappy pace, the film sensibly keeps its human actors front and centre, establishing a high-stakes showdown that revels in its excess. Although gladly gory, there’s little here that does not further the plot, even while Gordon and co. orchestrate what must go down as one of the most comically creepy sexual trysts in horror cinemadom. I mentioned in part one of this series that Frank Henenlotter was something of a master of grotesque sex but he has some competition here, with a disembodied head making bedroom eyes at Barbara Crampton’s bedroom body.

Herbert West makes for a fabulous anti-hero, simultaneously despicable and sympathetic, utterly propelled by his obsessive nature. Had he not designed a serum that can rekindle the dead, we might just as easily envision him obsessively plotting his designs in some other specialist field, be it restoring cars, acquiring obscure vinyl, or attending a Linux Convetion. Combs finds a nervous energy and intensity for West and the film readily feeds off of it. Re-Animator offers gory spectacle, sensationalist thrills, and genuine laughs in sequences we might never have expected. It also settles on a certain tragic tone, knowing full well that such power in the hands of man will only exacerbate suffering- dragging the tortured dead into extended purgatories and too many of the living into early graves.

Thirst (2009) Chan-wook Park

I’m a big fan of South Korea’s Chan-wook Park, indeed I think he’s one of the best directors currently working anywhere in the world. His career is marked by tales that count the cost of blood, but with Thirst he takes things a little further by establishing the shedding of blood as the necessary stuff of life itself, at least for one man. A loose retelling of Émile Zola’s, Thérèse Raquin, Park’s film is also a loose adaptation of vampire lore, combining the two into a blackly-comic, and appropriately fanged, morality play.

A Catholic priest (Kang-ho Song) survives a deadly and mysterious disease but finds the consumption of human blood necessary to continue staving off its effects. A bizarre side-effect of living with the disease is that it bestows certain super-human powers. As he struggles to deal with this most unusual development in his otherwise frugal life, he gains a posse of religious followers that seem to have him pegged not as an emissary of Catholic faith but as a new God entirely. Meanwhile he reconnects with a young woman (Ok-bin Kim) who has been trapped in a loveless marriage by unfortunate circumstances. As the priest struggles to acquire blood without succumbing to murder, he finds other corporeal passions rising up too and begins an affair with the young woman which eventually escalates into the murder of her husband.

Although freely indulging in vampire tropes, Park’s film is more concerned with Zola’s text, the supernatural elements merely heightening the irresistible tug of selfish pleasure and the treacherous moral slope that holds our characters in sway once the first small infraction has been committed. For all its doom and gloom, Park’s film is often riotously funny- finding gags in guilt-ridden, adulterous sex and projectile-vomiting gore, among other things. The real find here, Song’s quality as a lead actor already well established, is the gleeful performance of Ok-bin Kim as the henpecked wife turned unchained explorer of long-subdued passions. She blends a vulnerable, childlike sensibility with a fearless sexual bent that allows her character a transformation somehow even more remarkable than her lover’s journey into vampirism.

The film’s finale, and the culmination of the work as morality play, invokes the final shot of Ran but, where Akira Kurosawa suggests that each man stands alone in the face of existence, Park suggests there may be nothing lonelier than a couple. It’s Stoker, Zola, Strindberg, and Kurosawa but above all else, Thirst is pure Chan-wook Park.

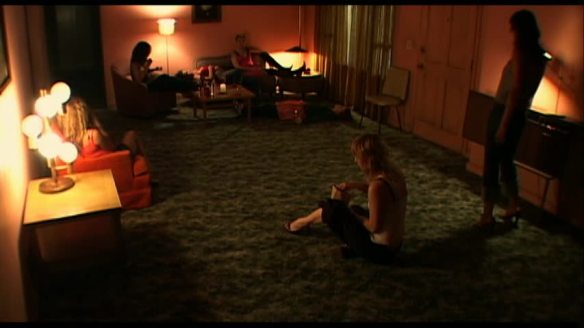

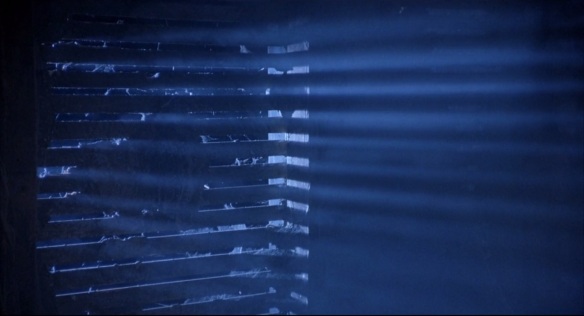

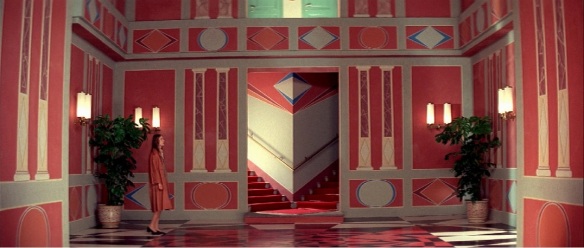

Inland Empire (2006) David Lynch

David Lynch has moved around a lot between mediums within a lengthy career that has continually surprised. Although first and foremost recognised as a filmmaker, he has, in the last two decades, gone the best part of a decade between features before then unleashing a couple of beasts to keep his fans thrilled. In between he’s not disappearing into the ether, but producing short films, documentary art projects, and music. In this fashion, he has cemented himself as one of America’s foremost multi-media artists, following his own whims and continually reinventing his work while maintaining a familiar thread through it all.

2001’s Mulholland Drive was going to be a difficult act to follow. It had a popular crossover appeal while also embodying absolutely, indeed even refining further, the dream-logic tapestry that underpins Lynch’s film theory. Sensibly, he took his time although with five years elapsing, warning signs flashed: Lynch declared that film was dead and digital cinematography would be his new muse. Inland Empire approached: all three hours of it. It would reunite Lynch with his Blue Velvet star, Laura Dern, but the production’s other details sounded so ambitious, so demanding, that it was hard to imagine what the final project might actually be like. Would this be the film that we’d nod sagely through, cite our admiration, and then acknowledge that there were failings fundamentally born of the project’s design that it just couldn’t overcome? Okay, maybe it was just me gearing up for that potentiality. But then the film came out, bitch-slapped me, and strutted away leaving me clinging to the arm-rests.

To be fair, I don’t think any amount of preparation could really have set me up for Inland Empire even as its subtitle, ‘A Woman in Trouble’ proves an accurate summation. It is certainly Lynch’s thorniest feature, even more demanding than the willful obtuseness that pervades Fire Walk with Me (some might argue that Dune is still harder to watch. Sting’s golden underpants are indeed a potent hurdle). At times this feels like a film that escaped Lynch’s grasp, pushing itself out from him, first through a series of shorter vignettes (Rabbits and Darkened Room) before finally coalescing, into one monstrous feature. Your instructions are simple, put aside the three hours, because they are well-spent, crank the volume up as loud as your system and neighbours will allow (actually, ignore your neighbours), and step aboard a magic-carpet ride to some strange threat yet to be determined.

Inland Empire is again, a film about film, but where Mulholland Drive traced tragedy amidst Hollywood’s dream factory, this later film feels like it begins with tragedy and traces a nightmarish path into deepest, purest despair. A Polish film production is shut down, due to some horrible happenstance of an ill-defined nature. A new production, in America, later starts and an actress (Laura Dern) scores the lead. She begins an affair with her co-star (Justin Theroux) and soon finds her sanity fraying, as the details of the production and her own life begin overlapping, reversing, interchanging, and conjoining. Laura Dern is a woman. She’s in trouble.

For anyone familiar with Lynch, a narrative re-cap is basically irrelevant, the meaning is layered through a thousand little details, textures, and edits- a logic that specifically evades words and rationality. What is not as familiar for Lynch fans, is the immediacy that digital cinema imbues in his images, how it allows him to structure his film in an ever more radical fashion, capturing accidents, the camera uncovering as he explores. And so Lynch’s longest feature is, in many ways, his most intimate. It catapults the viewer through an identity in its death throes. It is here that Lynch exposes most fully the quiet, terrifying loneliness of a human in distress, evoking and sustaining what many of his previous films could only find quiet glimpses of (I think particularly of Fire Walk with Me here). It is probably Lynch’s single greatest film, although I think many people, myself included, are slow to make that judgment because we’re wary to tread back into it too often. As far as scary movies go, this occupies some special tier, a small plateau ahead where almost nothing can bear to tread.

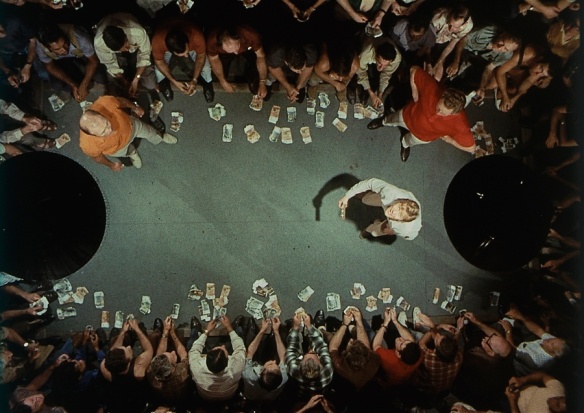

Wake in Fright (1971) Ted Kotcheff

“All the little devils are proud of hell.”

So what film could possibly follow Inland Empire’s cavalcade of the unwell? How about a Christmas movie? Well, a movie set in Australia at Christmas- sun-bleached and suffocating. It would be tempting to dub Wake in Fright as, ‘The Hangover: Australian Edition’, if only to tempt in unsuspecting victims, but I couldn’t in good conscience unleash this beast on someone who was unprepared. It is the tale of man succumbing to his animal self in the Outback and easily one of the more upsetting films I’ve ever seen. And that’s not a bad thing. The film was nearly lost, unseen for decades, with only a few sub-par prints rotting in storage around the world until a single, quality negative was found, marked for imminent destruction. One wonders if perhaps the Australian nation conspired to erase the film to protect their good name, but as is the fashion with serious interrogation, this film tells us about more than simply Australia.

Losing all his money in an ill-advised gamble, a school-teacher on his Christmas break finds himself adrift in an isolated town. He is taken in by a few of the locals, his planned one night there turning into a five-day, beer-soused nightmare of self-discovery- of both himself and the base impulses that link all men. The Australia shown here seems so remote and so wild that its feral nature seemingly seeps into its inhabitants. Living in dusty, small communities, a male-centric culture emerges, defined by drinking and dull thrills. The “hospitality” that finds our protagonist being fed free beers is really a need for everyone to conform, to exist on the same level so that no one need be reminded of every failure that underpins them.

Opening with an almost jovial tone, aided by a bouncy musical theme (which also accents the film’s close as a kind of wicked joke), Wake in Fright soon descends into uninhibited nausea, throngs of sweating bodies seeking to forget, sexual dysfunction, and social loathing. Without a Toecutter in sight, this portrait of rural despair suggests something vastly more distressing than the dystopian hyperbole of Mad Max. It’s curious then, that a Canadian, Ted Kotcheff (best known for directing the first Rambo film) is at the helm of it all. It begs the question, “just how accurate is all this?” But where Wake in Fright succeeds is that although it resides in the geographic specifics of Australia, one can imagine the small, insidious boredoms that breed its terrors thriving anywhere where isolation and lack of amenities are the norm.

As a final warning, those distressed by animal cruelty may wish to pass. The film closes with a note from the producer clarifying that the sequences of kangaroo hunting captured here were to take place anyway, and were not staged for the film. In fact, so appalled were the crew with the hunt they found themselves filming, that they reportedly staged a power-failure just to call a halt to the thing, while the drunken hunters continued taking potshots at already grievously maimed kangaroos trying to crawl for cover. Under advice from animal cruelty advocates, Kotcheff and co. were asked to leave as much footage as they could in the final film, simply to show the barbarity that formed the norm of professional kangaroo hunters’ sport. To that end, the sequences in the film are highly protracted, crossing into the seemingly gratuitousness. They gel well with the rest.

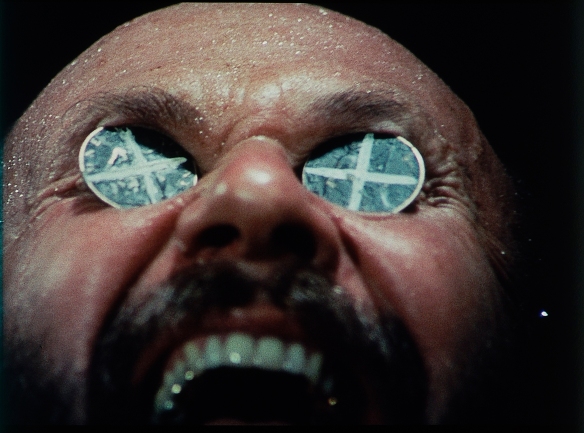

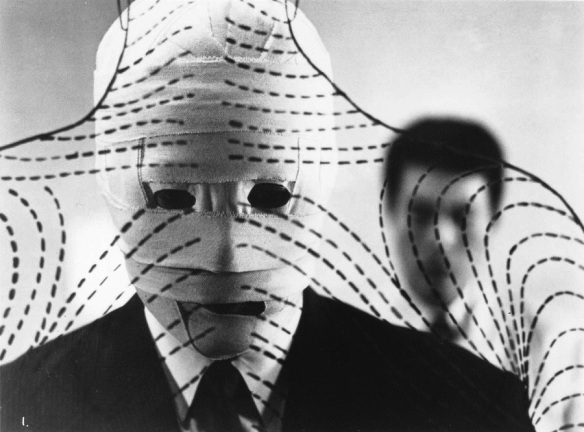

Island of Lost Souls (1932) Erle C. Kenton

Although I say this with absolutely no research (which always makes for the best grand pronouncements) I can’t imagine there have been many films rejected by the British Board of Film Censors for being, ‘against nature.’ As backwards as film censorship is as a moral practice, that’s a pretty cool feather for any film’s hat and Erle C. Kenton’s 1932 horror film, Island of Lost Souls can make that boast. Made by Paramount, looking to cash in on Universal’s recent successful forays into horror cinema, the film takes H.G. Wells’ The Island of Dr. Moreau as its genesis before gleefully stripping out much of that work’s finer points to instead ratchet up the horror and the sex. A release year of 1932 allowed it to slip by Hollywood’s own censorship code, which would not come into official effect for another year or two.

As with many of Hollywood’s early talkie horror films, this isn’t a particularly high-minded or lavish production. It’s pure exploitation and it’s very happy with that. What makes it fascinating, and compulsively watchable, is the way exploitation was honed in those days, when you still had to sublimate it into a variety of other channels rather than just flinging nudity and cascades of gore at every scene. The film’s jungle-sets are claustrophobic and simple. The story-line whips by like a child on their first unassisted bicycle ride, petrified by the thought of slowing down even for a second because that might bring the whole thing to a crashing end. And then there’s Dr. Moreau, played with reserved menace by Charles Laughton, then only at the start of his film career and still enough of an unknown to be attainable by the producers of a film such as this.

What really sets Island of Lost Souls apart though, are the make-up effects and the sadistic veneer the whole thing carries. The beast-men, Moreau’s animal/human hybrid experiments, are a pathetic, cloistered mass of deformed flesh and stupefied minds. They huddle and quake in Moreau’s presence, dumbly reciting platitudes as scripture until they realise Moreau holds no law in regard when his own interests are threatened. The rebellion comes swiftly and horrifically amidst horrific screams. Without showing a single explicitly grisly scene, the clambering throngs of beast-men sweep up Moreau so that he may experience his own, self-proclaimed ‘House of Pain’ from a whole new perspective.

There is a sense of outrage to the whole project, a sense of real intensity to its otherwise threadbare recounting of Wells’ tale that passes through to the transgressive. Laughton’s Moreau is so brilliant a mind and so appalling a human being that he courts no sympathy, and yet the final descent still conjures up images that suggest an end too awful for anyone or anything. Island of Lost Souls feels like a companion-piece to another shocking 1932 odyssey, Tod Browning’s freak-show drama, Freaks. Browning’s film is undoubtedly more formally extreme, a combination of exploitation and genuinely curious exploration that feels impossible to replicate now, but Kenton’s film achieves nearly the same level of outrage using special effects and judicious production, pointing the way forward for many of the best of horror cinema that would come in its wake.

The film also features a small role for Bela Lugosi, as the shop-steward, as it were, of the beast-men, The Sayer of the Law. It’s not really a major part of the film as a whole, but I find Lugosi’s participation in nearly anything, aside from the unreserved success of Browning’s Dracula, to be a point of some bittersweetness. His talents wavered from role to role, the product of a tumultuous life, but his presence remained unscathed, even in the most garish and ridiculous of projects until the very end, when drug addiction and Ed Wood, Jr. were all he had. He has, in my mind, outstripped his characters and become a figure of genuine tragedy which then bleeds back into his fictitious personas. His small role here is just another in a series of hammer-blows to my senses.

Witchfinder General (1968) Michael Reeves

Although subject to mismanagement, critical attack, and misguided expectation, Witchfinder General has eventually been recognised as one of Britain’s finest horror films. Hedged slightly in truth but heavily in fiction, it dramatizes the reign of terror of Matthew Hopkins, the self-appointed Witchfinder General who took it upon himself, during the English Civil War, to travel from town to town detecting and punishing witches: which is to say, he briefly made a living preying on religious paranoia and social upheaval, to horrifically torture, maim, and murder a lot of woman. About 300 or so in a two-year span, according to Wikipedia. This makes the film an unusual ‘based on a true story’ affair since its brutish violence and sadism are reasonably accurate but the notion that Hopkins actually paid for his crimes was not. Reality sometimes just isn’t a good script-writer.

One of the major sticking points for the film is Vincent Price’s role in the lead, as the villainous Hopkins. His inclusion was directly in opposition to hotshot young director, Michael Reeves’ wishes and was imposed at the behest of American investors, James H. Nicholson and Samuel Z. Arkoff, of American International Pictures (AIP), who ironically, originally only invested in the film as a tax write-off. Price was their biggest contract star and they wanted him in the lead to bolster the American marketing effort. It turned out to be one of cinema’s more pleasant accidents. Though Price and Reeves were apparently at each other’s throats for the entire production, both knowing the other didn’t want them there, what emerged is arguably Price’s finest acting role in a jam-packed career. It took a while for that realization to emerge though, as Price ended up, under Reeves’ direction, playing entirely against his usual ‘type.’ Gone were his campy flourishes and thespian brooding. Here Price is deathly calm and utterly intense, his every word and action laced with venom. His Hopkins is a cowardly opportunist and a despicable tyrant. A man genuinely disinterested enough in basic human mores to push ever harder to carve out a legacy of bold forgery.

Shot on sparse sets, and utilising England’s unassuming countryside for fullest effect, Witchfinder General depicts in glimpses, a nation in freefall, tearing at the seams under weight of war and uncertainty. With men dying by the score on battlefields to forge the nation’s political identity, anxiety and paranoia took root in small towns and villages, where fear that the Devil and his assistants might sense new opportunity seemed an all too plausible possibility. Of course we’re left in no doubt that if the Devil has any role here, Hopkins is his emissary. Reeves’ film depicts the affairs of witch-hunting with an unsparing eye, lingering on torture and hopeless death. This facet of the film didn’t exactly make it many friends in the late-sixties. Still there’s no denying the intelligence of Reeves’ film, and its broader theme of the darkness mankind can breed when it lets fear take the upper hand. He would never see the film’s success, dying of an accidental drug overdose mere months after the production closed.

In its native England, the film was censored for its violence. In the United States, it avoided such treatment but was instead affixed with ill-judged addenda to try and loosely tie it in with a larger cycle of films AIP had produced, centring on Poe adaptations with Price in lead roles. As part of this treatment it was re-titled Conqueror Worm which, while inarguably evocative, doesn’t really make much sense. It took many years but the film eventually found itself restored and re-assembled, shirking off the opportunistic additions of its American incarnation and re-instating the elements forcefully shorn from its UK release. In time it would be recognised as a classic of horror cinema, but its more earthy elements quickly struck a chord, producing many knock-offs that focused more on sadistic sexual violence and less on character study. The most famous is probably Mark of the Devil, made in 1970 and luridly marketed at the time with promotional sick-bags etc. It’s the kind of film that is every negative thing people claimed of Witchfinder yet with curious redeeming features of its own, namely stately location photography and a couple of impressive directorial flourishes to counterpoint the pulled tongues and popped eyeballs. So if you’re looking for something a little less classy once Witchfinder’s end credits roll, consider that another suggestion.

And that makes 31 films!