Valerie and Her Week of Wonders (1970) Jaromil Jireš

In the 1960s there was an explosion in the cinema of Czechoslovakia that was heard around the world. Although the nation had a rich cinema prior to this period, and one I’d very much like to explore in the future, this period ushered in what became known as ‘The Czech New Wave’ and formed a Golden era whose influence still resounds. Though under the auspices of a repressive Soviet government, the artists of Czechoslovakia found themselves with an increased artistic freedoms compared with many of their neighbours, and pushed the boat out even further when they recognised that Communist censors had some difficulties spotting aberrant messages if they were veiled in the blackly comic or dressed as the absurd.

Many great talents grew out of this period, including a few who made it to Hollywood and helped shape their New Wave in the 70s (One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest director, Milos Forman, for example) but for the season that’s in it, I’ll focus on Jaromil Jireš’ eerie vampire tale, Valerie and Her Week of Wonders. Stating the obvious early on, Valerie has little to do with the legacy of Bram Stoker’s novel, or with vampire lore generally. It is, as we might expect, a number of different stories and sources intertwined and overlapped, creating an odd web of image, sound, and intimation.

Young Valerie finds herself the subject of much strange attention, her earrings stolen by a young man, a vampire potentially living in her yard, priests calling all the virgins of the town for a sermon, and her grandmother apparently in a pact for eternal youth sealed with blood. Gliding along on ethereal narrative strands, the film’s lush musical compositions meld with unusual visuals, hedged in the natural, flowers, water etc. that belie the rigorous composition behind them. The film creates multiple planes of interest, with Valerie’s own quest set against many unknowns- the weight of her family history, of the town’s own unnatural rhythms and so on. Reminiscent in part of the great Russian director, Andrei Tarkovsky, the film’s compositional sense creates tensions and allusions within the same frame, offering the eye many points to pursue.

Or to put it another way, Valerie and Her Week of Wonders is probably the best film ever made about menstruation.

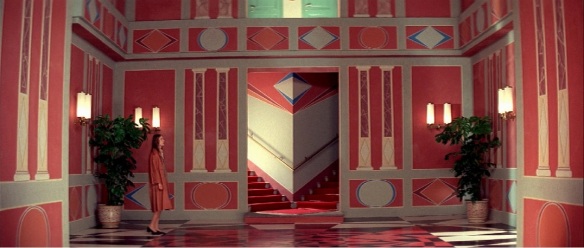

Suspiria (1977) Dario Argento

I know, I know, if there’s one name that keeps popping up again and again here, it’s that of Monsieur Argento. It can’t be helped really, he’s kind of a big deal in horror cinema and this will be my first, and only, pick which places him front and centre as the director. It’s an obvious choice I guess, Suspiria has carved out a pretty sizeable niche in the annals of cult cinema, but it’s a film that I have grown more and more fond of with each viewing. There’s plenty to enjoy here, but sometimes it’s easy to get hung up on the film’s great sense of surface and forget just how strange and provocative a heart lies underneath.

Argento got his start as a director popularizing the ‘giallo’ sub-genre of film. He pretty much made the genre what it is today, moving it into the semi-mainstream and providing what are widely regarded as the very best films of the entire scene (The Bird With the Crystal Plumage, Deep Red, Tenebre and so on). Those films are not hinged on the supernatural though, so Suspiria represented something of a shift in his career. The film moved away from the recipe for most of Argento’s previous films: a belaboured protagonist seeking to unveil a murderer, the key to the mystery usually couched somewhere in his own memory, while all around him people die in horrific ways as the killer closes in. Instead Suspiria follows a young woman as she attends a ballet academy in Freiburg, Germany. That’s all very well, ballerinas must learn to ballet somewhere, I suppose, but it turns out this place is also the coven of a powerful and ancient witch and no amount of pliéing makes that okay.

The film’s pitch is nothing less than delirious, from start to finish. The sets hang in abstract space, boasting décor, colours, and shapes that defy their nominal role as functional objects and the music, provided by prog-rock group Goblin, is cacophonous and unrelenting, often being given primacy over dialogue or other diagetic sounds. It’s easy to get caught up in this surface madness, the sheer titanic pull of Argento’s aesthetic, but there’s still a tendency to prescribe that the film works despite its narrative failing, rather than because of it. Argento’s earlier films, for all their outlandish content, maintained tight narrative controls, offering very explicit explanations for their every motion and gesture, with red herrings composed as carefully, or perhaps even more carefully, than the final denouement. Suspiria is the film where he let go of narrative, instead pursuing something more intangible and fractured.

Suspiria is a nightmare, unfolding in broad strokes of cinematic excess. It draws you in with its brazen swagger but its finale closes tight on the viewer, a fantastic success in wayward logic and casually outlandish special effects. While not everything works perfectly here, the odd childish whisperings of the ballet school’s student body, for example, would make sense were they all 12, but they’re all adults…Argento just never changed the script when he altered the girls’ age upward for casting, Suspiria remains a triumph of experimental form, demonstrating avenues of madness not yet explored by heavyweights of psychological horror and surrealism. If giallo largely depends on stunting audience perspective by only allowing us to see the hands of the killer, or their blade, until the final reveal, then Suspiria alternately denies us all of our various senses, reveling in switching on and off various functions of cinema to leave us swirling in its wake. The finale then clamps tight around us, a genuinely fearful spectacle that parlays the film’s fractured narrative into a deadly stand-off against illogic itself, a witch in our presence.

Suffice it to say, Suspiria remains one of the most visually and aurally insistent films ever made, but it is also one of the truest works of filmed horror we have.

Fiend Without a Face (1958) Arthur Crabtree

The 1950s was a glorious time for science-fiction and horror cinema. Sure, a lot of it is cheap hokum, but let’s be honest, a pig in a dress is still a pig, and once you’re on board with that fact, everyone can have a lot more fun. Which I guess, is my way of saying, most critically-acclaimed science-fiction and horror cinema is just a more expensive, shinier pig in a fancier, frillier frock. In any case, there’s a reason why people keep returning to these movies and that they are constantly being re-issued, moving from Laserdisc to DVD to Blu-Ray: because they’re just fun.

Originally paired as the B-side of the more lofty Boris Karloff picture, The Haunted Strangler, Fiend Without a Face is a monster-flick of almost unrivalled goofiness. Its plot is a thing of absurd beauty, involving leaked atomic energy that produces mental monsters that prey upon the spinal cords of their hapless human victims. At first they remain invisible – a hilarious cost-cutting exercise as much as anything – but later they become manifest as disembodied, flying brains with spinal-cord tails and insect antennae.

The special effects, involving impressive bouts of stop-motion animation, have a delightfully primitive feel and take flight in the film’s final third as the evil brains are dispatched left and right with bullets, axes, and whatever other instruments come to hand. The effects for this are so gleefully gory that questions were raised in the British Government about how such a film ever saw the light of day. There was some public outcry too, and the film had already been trimmed by the censors before if had been released anyway. Granted, by modern film standards Fiend Without a Face might seem tame, but it looks like little else of its time with its violent abandon, as if the director (Crabtree felt the project was beneath him from the get-go) was trying to mercilessly slay the stupidity of the whole thing right there on the screen.

Fiend Without a Face mischievously repels intellectual inquiry, despite the fact that half the cast are murdered by manifestations of the human mind. I mean, that’s gotta be at least kinda Freudian? Right? What’s more important is that it easily surpasses the limits of its financing and production to reign supreme as a work of absolute, unapologetic entertainment.

I Walked With a Zombie (1943) Jacques Tourneur

It’s amazing what you can do with a strong vision, some canny financing, and some talented cohorts. It certainly can be the recipe for great cinema and we need look no further than producer, Val Lewton as proof. Through the 40s he released a string of low-budget genre flicks that remain influential to this day. No one undoes the crass hierarchy of A and B movies better than Lewton, who helped shape a supremely cinematic group of films on topics and budgets that most others would only use to produce cynical filler. Of course it helps when you have the likes of director Jacques Tourneur and script-writer Curt Siodmak on your side, both established as talents in their field but not yet pegged as notable names in cinema history. Lewton would help them cement their case as they helped him do the same.

George A. Romero’s Night of the Living Dead brought the zombie movie into the modern, marrying a tense narrative with gory spectacle and critically, although perhaps accidentally, a racially charged subtext. Prior to that film, Tourneur’s I Walked With a Zombie stands as perhaps the greatest ‘classical’ zombie flick, although it is, in fact, something much more complex than that. Utilizing an exotic locale, weaved with voodoo folklore and Tourneur’s penchant for ambiguity, the film unfolds a very strange tale about a Canadian nurse, Betsy Connell (Frances Dee) who is brought to a small Caribbean island to care for a plantation owner’s wife. The wife is apparently the victim of a spinal injury that has left her bereft of identity and free will. A zombie? Perhaps? Investigating the inhabitants of the island, Betsy uncovers an illicit love triangle and a rich vein of voodoo practice, which may or may not be harnessed by elements on the island to shape the larger society.

The beauty of Tourneur’s film, as was his wont, was that he offers the viewer two parallel folds within the same narrative. I Walked With a Zombie may simply be a sweltering, fantastical soap-opera about an unusual medical event or it may be a portrait of Black Magic run amok. Either version suits, and the film supports both comfortably. The most interesting elements reside in between the rational and the supernatural, the question of identity and free will and of religion and folklore’s role in a rational society. Shot in high-contrast black-and-white, with the darks of the frame often clambering to suffocate all light, Tourneur’s film is a brilliant example of high-concept filmmaking, tackling seemingly outlandish subject matter to expose instead very real concerns and ideas.

As an interesting side-point, Portuguese director Pedro Costa states that his second feature, Casa de Lava, is a re-envisioning of Tourneur’s. It may be lighter on the portentous omens that inform this ongoing list’s sensibilities, but it remains an intriguing and rewarding film too. So feel free to track it down.

Tetsuo: The Iron Man (1989) Shinya Tsukamoto

No list of scary movies would be complete without something from David Lynch and, I admit, he’s on the way. In the meantime I’ll dwell on this particular oddity from Japan, Shinya Tsukamoto’s critical breakthrough, Tetsuo: The Iron Man. I mention Lynch because, when I first saw his feature debut, Eraserhead, I didn’t really think anything else out there could be much like it- its inky-black photography, its freeform narrative, its unyielding sense of anxiety etc. Although quite different when you get down into the (in this case, literal) nuts and bolts of it, Tsukamoto’s film is perhaps the closest relative we have to Lynch’s resolutely strange film.

Tsukamoto got his start in experimental theatre, which led him to experimental cinema in due course. That experimentation was hedged heavily in the burgeoning ‘cyberpunk’ aesthetic that was gaining popularity in the fringes of Japanese media culture throughout the 1980s. It’s little surprise that one of his cohorts was Sogo Ishii (now Gakuryū Ishii) who, in 1985, directed Halber Mensch, an hour-long film documenting a recent trip to Japan by Germany’s Einstürzende Neubauten. If you’re familiar with that musical group’s aesthetic, especially their work at this time, where clanging metal and the incessant whine of angle-grinders were integral parts of their soundscape, then you’ll have a good idea of what Tsukamoto’s film offers.

Ostensibly a portrait of urban alienation and man’s growing dependence on technology, Tetsuo follows a nondescript salary-man who finds that his body is slowly and agonizingly turning into metal. With little interest in a coherent narrative, the film resolves into a series of dizzying chases, paranoid asides, and gory transformations coupled with a booming soundtrack of chattering metal and pounding percussion. The editing is frantic, often used to create stop-motion effects or simply to create grander fractured motion and disconnect. Rather than elegantly and logically unifying disparate shots as classical editing theory dictates, Tsukamoto instead uses it as a whole other language separate of image and story, flinging the viewer about within the world. Given how insistent and ultimately how abstract, not to mention how unpleasant much of its content is, the film is unsurprisingly divisive. Suffice it to say, those who have seen Tetsuo will always remember it.

Fright Night (1985) Tom Holland

One night while Charley Brewster (William Ragsdale) is making out with his girlfriend, Amy (Amanda Bearse), he gets distracted by events next door. Two men seem to be moving into the old, abandoned house there. That might not be so strange except that it’s night time and the first piece of furniture they bring with them is a coffin. A fan of old-school horror films, Charley knows what that must mean: there’s a vampire next door! Still, at least vampires need to be invited in to invade your home, so imagine Charley’s chagrin when his mom asks him in for a nice cup of tea. With all his friends thinking he’s nuts, and the neighbourhood vampire well aware that he’s been found out, Charley’s in quite a pickle.

Blending genuine thrills with effective comedy, Fright Night remains one of the most lovable of 80s Hollywood’s teenage horror outings. Tom Holland’s film is informed by a love of old-school horror cinema but brings it hurtling into the 1980s with grand aplomb. The special effects are excellent, admittedly picking clean the bones of Rick Baker’s trend-setting work in John Landis’ An American Werewolf in London, and the film gleefully ups the ante with not simply a vampire, but a bevy of other monsters too. Although crystalized in that way that 80s fashion and music can’t help to do, Holland’s film remains fresher and more fun than most of its peers. It relies little on star power or passing trends and instead harnesses the best timeless qualities of its material, marrying horror and comedy with young-adult rites of passage and friends-forever shenanigans.

For the first part of this series click here

For the second part of this series click here