In brief: A powerful vision of Japanese post-World War 2 fallout, allying pulpy visuals and plot elements with an engaged voice *****

Source: Hulu+

The trope of post-war women, In Europe and Japan, turning to prostitution, is so well-worn that mere allusion to it can render even the most sensitive and well-meaning film utterly tedious. Luckily, Seijun Suzuki has very little interest in sensitivity and came into his own by specifically avoiding the dull checklists that typified the industry in which he worked. So when he makes a film about that very subject, a gang of plucky women eking out a living through prostitution, it quickly sets itself apart. It does not simply avoid the norm, it establishes its themes and concerns as if no one else had ever even considered them before.

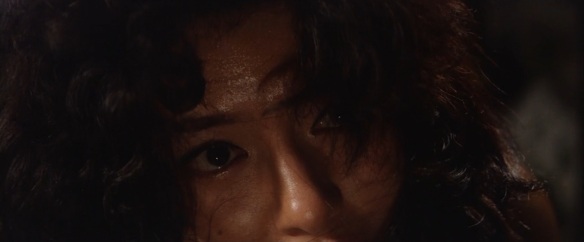

Our “heroes” are a gang of young prostitutes, helpfully colour-coded, who use their numbers to fend off outside threats. With the intrusion of a man, a returning Japanese soldier (Jô Shishido, rising to a more demanding role), the women’s values begin to crumble as their own sexual longings begin to supplant the capitalist veneer they themselves imposed.

Gate of Flesh is a film of antagonisms, all straining in opposition, creating a radical space in which a vein of genuinely fresh drama emerges. Even as the film openly invokes sexploitation elements, an unsurprising mainstay of Nikkatsu’s 1960s roster – they specialised in cheap and plentiful productions, mainly aimed at the youth market, and by the 70s would switch exclusively to producing soft-core porn features – it uses them to underpin a caustic social message, cultivating an unusual counterpoint of content versus theme. The sight of naked flesh being whipped here is less pornographic and more aligned with a society debased to savagery.

The women utilize sex only for money but find pangs of their own innate sexual desires distracting them. They develop a code of rules for their gang, to try and root out these gnawing urges, but their own laws eventually undo them. The occupying Americans are reviled yet vital, providing law, order, but also paying customers. Even religion is sullied, destroyed under the weight of earthly want. Meanwhile Japan is both shamed by its defeat, condemned both for being too soft to win the war while also being too hard and rigid beforehand, prompting the war in the first place. Its returning soldiers share the same condemnation: fools who fought a pointless war and also cowards who lost it. Perched atop these oppositions, the film’s wildest, most rambunctious moments are also where it is most vulnerable- exposing raw nerves and providing a supremely humanist account of Japan’s post-war plight.

Suzuki further refines this template with clever use of superimpositions. They are no longer the muddled visions of the drug-addled, as in his previous Youth of the Beast, instead they are the intrusions of memories and pure ideals that are, by their illusory nature, now isolated and redundant amidst the cacophonous and terrible reality. That reality, built loud and gaudy with Suzuki’s preferred pulp inflections, is entirely consistent and perhaps the film’s greatest triumph. The art design, by Takeo Kimura (a major contributor in many of Suzuki’s best-loved films), is remarkable. Theatrical effects are often employed – in one indoor scene a spot-light follows a prostitute as she gets undressed – and they imbue an Expressionist edge. The sets zero in on the sweaty bustle of a defeated Japan and, in their intricate design, offer countless paths through which the actors can scurry. But despite fervent movement, they are all unknowing rats trapped in a cruel and suffocating maze. Under Kimura’s eye, every frame enshrines desolation and feral want.

Suzuki’s vision of post-war Japan, finds it greedily picking through and cannibalizing the tattered remnants of its former self. It is an eye filled with both sympathy and self-loathing, and it stands Gate of Flesh alongside the very best of war cinema. Needless to say, it may also stand as Suzuki’s own finest achievement.