In Brief: Gone Girl fails as storytelling, allegory, and feminist agit-prop and it feels like it takes many, many hours just to do so. It’s only barbed message is that David Fincher can actually do worse than Panic Room. *

source: theatrical showing

Sometimes I feel like a terrible curmudgeon. It’s true. People rant and rave about films they think are just the absolute best – The Shawshank Redemption, Pulp Fiction, The Dark Knight etc. – and I think, “those films are okay…mostly.” I experience a lot of disconnect from populist audiences but I’m generally not too out of step with things. For example, if everyone loves David Fincher’s latest, then I’ll probably enjoy it too, despite buttressing my praise with a few extra caveats. He’s usually a solid bet for slick entertainment. But oh boy, did I hate Gone Girl.

On its opening weekend, the film is rocking an 8.7/10 on the IMDb and an 87% approval rating on film-critic aggregator, Rotten Tomatoes. Now sure, Rotten Tomatoes is a site that reminds me that 99% of film critics seem to literally know nothing about film (and sure, for the few who read this, I’m probably no better, but at least I’m not financially recompensed for being a mouth-breathing illiterate), but the point remains: people love this film. They love David Fincher. He’s so exacting! He’s so precise! He’s so clever! And funnily enough, earlier this week, having never heard him speak about anything before, I caught a radio interview with Fincher and he did sound quite thoughtful, careful, and intelligent about his approach to this project. All of which only makes the final product all the more baffling.

I’ll gladly acknowledge that Zodiac, the best of Fincher I’ve yet seen, is a very good film, albeit with porn-y, slow-mo murder sequences that were in really poor taste. It’s efficient and entertaining, and condenses an interesting story into an easily digested product. That’s where Fincher excels. He makes solid entertainment with little artistic thrust. I doubt I’ll ever learn anything from one of his films. Even Fight Club came a little too late for me and I was already through the most pronounced of my teenage nihilism and existential angst. Looking back, it’s pretty shallow anyway, though often funny. His work is all surface and plot mechanics. He is incapable of pushing beneath to reveal what might be hidden. And to that end, Gone Girl a perhaps an inevitable failure, because it specifically seeks to enumerate two planes: the visible surface, and a swirling darker underbelly, unseen but inhabited by all.

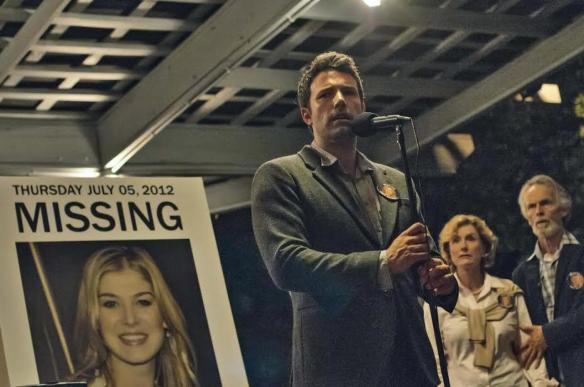

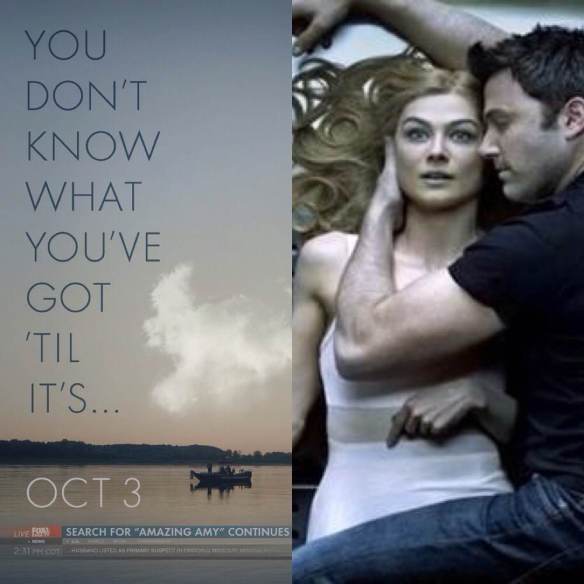

Nick and Amy Dunne (Ben Affleck and Rosamund Pike, respectively) seem to be the dream couple- affluent, well educated, loving, and successful. Yet one day, when Nick returns to the house, he can’t find Amy anywhere. A table is overturned, broken, and a telltale spot in the kitchen suggests blood was spilled. But there’s no body and no clear sign of a struggle. What is present is a slowly unfolding motive, as it turns out that affairs between Nick and Amy weren’t as golden as would first appear. Soon Nick is on the defensive, the prime suspect in a murder investigation that is attracting national media attention. Press conferences are called, rewards are offered, television interviews are scheduled, and the game is afoot- its goal to mold public perception and deflect insinuations of guilt.

The plot of Gone Girl is ostensibly interesting, and suggests many paths we might explore. Alas the final result is a poorly driven shopping-cart filled with second-hand merchandise and disappointment. David Fincher has always struggled with depicting ‘regular people.’ Granted, no one shows up to his films expecting well-rounded characters. He doesn’t do that. He never has. He doesn’t understand the quotidian. Even that which might seem banal- say, a newspaper artist doing after-hours research on a murder suspect, will grow into an epoch-spanning tale of obsession, à la Zodiac. So while the Dunnes of Gone Girl aren’t exactly average, their situation should at least cover ‘regular people’ feelings. After all, rich, white folk aren’t actually aliens, unless They Live was right all along.

Giving the benefit of the doubt, many key early scenes are recreations based on entries in Amy’s diary and, as such, are designed to highlight their own intrinsic subjectivity. Amy’s recollections feel an awful lot like wallowing in a Lifetime Movie, but we can presume that’s intentional. The issue becomes more troubling when the hollow dialogue and the players’ nervous, fidgeting bird movements sidle on over into elements that are ostensibly free from subjectivity too. Nick is placed centre-stage as the audience’s sympathetic guide but his “objective” plight is no more convincing. While we are welcomed to question whether or not he is a reliable authority, and we later learn he has much weighing on his mind, his discussions with the police, family, and the public all emit an irritating blitheness- the work of a scriptwriter trying to will a mystery into existence rather than leading us through one already in progress. With nothing vaguely human to set the foundations of the film, the storyline, which is frankly outlandish, whisks itself off into outer-space.

As is expected the production values here are high, with a typically impressive visual schema laid out in super-cinematic, ‘Scope’ widescreen courtesy of Fincher’s regularl cinematographer, Jeff Cronenworth. The colours are muted, typically set in blues and greys, exemplifying supposed domesticity. This, in turn, is offset against the lurid brights of the TV gossip-mongers as they throw their accusations. We get another score from Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross that is tonally appropriate but feels a little humdrum, all things considered. That being said, if I had to keep anything from the film it would be the soundtrack, as the rest is far more compromised. Major dramatic events are accompanied by hammer-blow throbs of cacophony, the bleating score pushing into over-drive to try and convince us that events might be interesting, intense, or even the tiniest bit surprising. Such unintended goofiness gels well with Fincher’s portentous count of Amy’s absence, using titles that begin with, ‘5 Days,’ before, after a few seconds, ‘Gone’ appears to finish the sentiment. It is a film that is adeptly produced but devoid of any character but its own mistakes.

In terms of the cast, Affleck acquits himself well, reminding us that half the jokes about his bad acting are behind the times or based on selective memory. Sure he’s been really bad in some really bad films, but here he proves he can step up his game in a turkey too. I’ll offer a vague ‘spoiler warning’ here before anyone ventures onto the next paragraph. Subsequent chatter requires acknowledging something that is revealed about halfway into the film. So while I find it difficult to imagine that anyone could find it surprising, although I know I’m wrong because I watched this in a sold-out theatre and people clearly were, and though the film’s end destination does not hinge on what I will reveal, if you want to see the film totally fresh, aside from knowing that I hated it, then go no further. This account is already hideously long anyway.

Rosamund Pike has the tougher task, trying to invest reality in a character that was pulled out of some ‘girlfriend from hell’ sketch. It’s difficult to tell how well she succeeds because judging her performance is a little like judging Anthony Hopkins in The Silence of the Lambs. His work was totally over-the-top but the film supported it brilliantly, unveiling him like some Universal Studios monster of yore. Gone Girl doesn’t realise that it is, in essence, a high-camp car crash, so Pike is afforded no such support for her similarly arch role. The rest of the cast fall into the background, laden with either uni-dimensional characters (i.e. Neil Patrick Harris and Tyler Perry) or roles that serve only to mechanically further the plot (i.e. cop duo, Kim Dickens and Patrick Fugit, the former’s good work being especially wasted).

What is more troubling than the film’s aching dullness is that it is ostensibly permeated by a rich vein of casual misogyny. To his detriment, Fincher’s later films generally only play at one speed, super serious, but, of course, there are jokes in Gone Girl. They’re just almost entirely based on flippant, sexist banter. Nick’s family never really liked Amy because she’s talented, spoiled, and wealthy. When we find out that she’s actually is an unhinged, psychopathic reincarnation of MacGyver, their hatred is obviously justified. She’s a manipulative succubus and silver-spooned ice-queen that drove her poor, laid-back husband to the brink and, as the premier emissary of female mores in the film, she is also a grander character assassination of all capable women. There are other women in the script, but they’re underwritten and working class- more relaxed and on Nick’s level. They wouldn’t try and get him to wear a tie and they don’t have no fancy book-learnings. Depressingly, the women in the audience laughed along to weak jibes about how stuck-up, prissy, white women are all manipulative, treacherous bitches who need to get what’s coming to them.

Now we might reject that Amy is a thinly-veiled accusation against all women of means by latching onto the suggestion that her scheme is a desperate attempt to re-assert her importance in a failing marriage. I really don’t think so but, if only to offer the film a shot at a less ideologically reprehensible theme, I’ll give it a shot. Gillian Flynn, the author of the original novel and the screenplay, clearly has her eye on this kind of discourse. A few passages of Amy’s dialogue do suggest that once upon a time, she tried to be a “good woman”, but as the pressures of life mounted and Nick drifted away from her, she realised that, despite her best efforts, her true lot as a ‘domesticated woman’, even one of means, would reduce her to the pathetic unless she took drastic action.

So perhaps the unquestioned, casual misogyny leveled against her elsewhere in the film exonerates her destructive mischievousness and she is, in fact, the hero of the piece? I’d be lapsing into the fondly poetic to claim that Flynn or Fincher’s work genuinely supports such a wickedly satirical conclusion even while it would be funny to imagine that the audience I sat with were being unknowingly indicted with each giggle they proffered. The substance isn’t there though, and I can’t help but be reminded that artists who have boldly made such inferences, Rainer Werner Fassbinder springs first to mind, could never deliver such a doddering, self-serious bore. Fassbinder’s The Marriage of Maria Braun, a vastly more nuanced work of feminist cinema, sets out in poverty-stricken WW2-era Germany, with the protagonist starving and turning to prostitution to make ends meet and it offers more laughs than Gone Girl.

Rather, the film’s conclusion suggests that, with the public eye looking on, unhappy, selfish people will actively reinforce their unhappiness, setting in place cycles of casual domestic brutality that will repeat forever more. A terribly dark conclusion…except that both parties are flipsides of a counterfeit coin.